Blood, Eggshells, and the Ephemeral Nature of Objects: A Conversation with Basse Stittgen

March 23, 2025 | Isabel Lotus

Basse Stittgen is an artist and designer based in Amsterdam, Netherlands whose work explores the intersections of matter, form, and transformation. A graduate of Design Academy Eindhoven, Stittgen has built a practice centered around rethinking waste and overlooked resources. He transforms discarded materials—blood, eggs, and natural polymers like cellulose and lignin—into sculptural objects that challenge conventional notions of permanence and value. His approach is both critical and poetic, forcing us to question the politics of production and consumption.

In practice, Stittgen’s work goes against the grain of the conventional "form follows function" philosophy and instead follows the principle of "form follows materiality." Unlike traditional design approaches that prioritize function, his work is a response to the inherent properties and histories embedded within materials themselves. A material is never just a material—it holds memory, decay, transformation, and power. Digital artifacts accumulate faster than we can process, but Stittgen’s work pulls us back to the physical world. He molds narratives, sometimes literally, into objects that resist disposability. If our digital and physical realities are bleeding into each other, Stittgen’s work serves as a tactile counterpoint. He reminds us that materiality can anchor us in an age of fleeting digital aesthetics.

Record made from discarded cowblood that plays the heartbeat of the animal.

The internet has turned aesthetics into currency. Aesthetic capital—the cultural weight carried by design, taste, and visual identity, now dictates belonging in the same way subcultures once did. Stittgen’s practice asks: what happens when materiality resists digital consumption? What if objects refuse to be flattened to pixels and trend cycles?

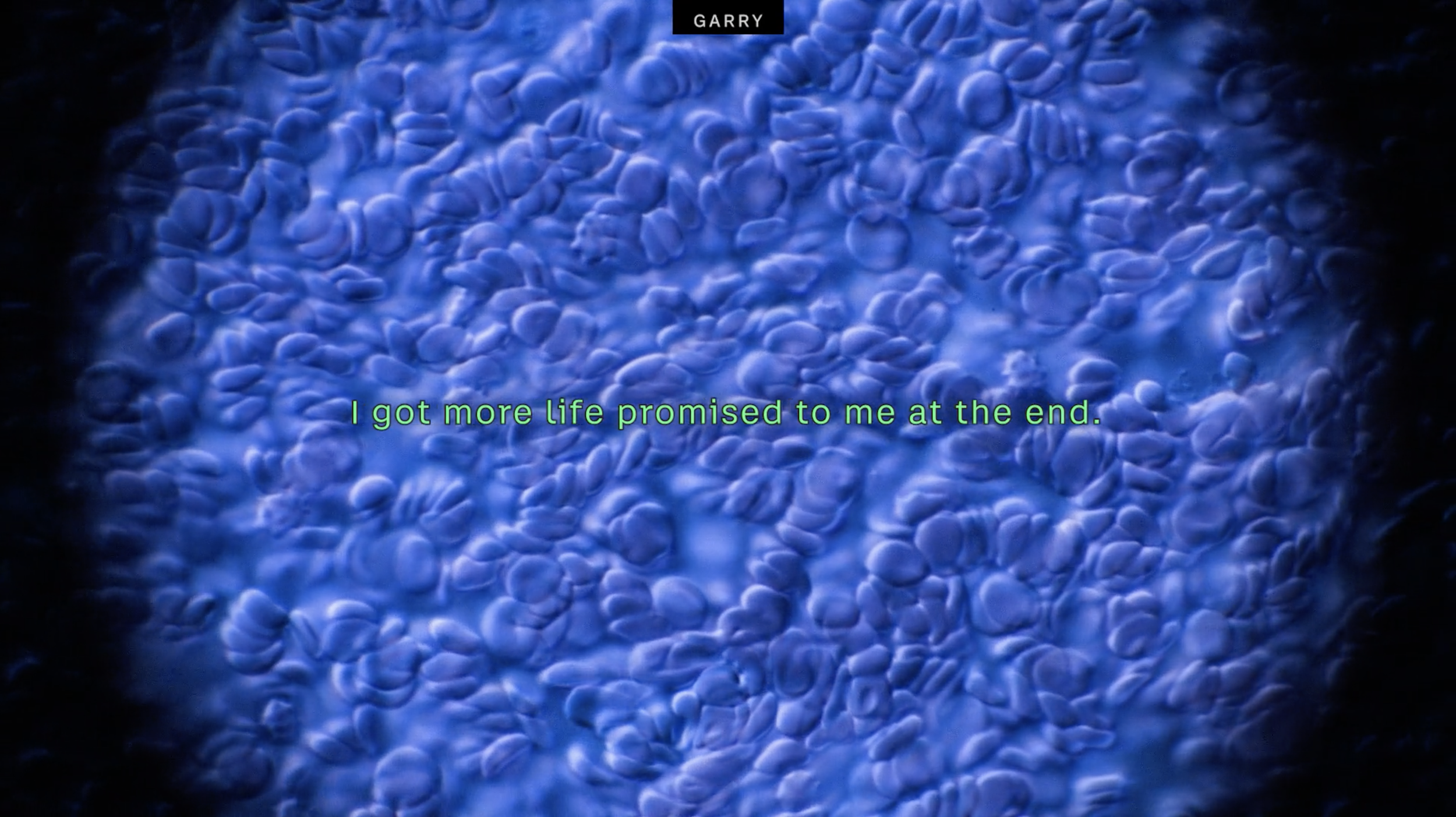

Blood Related, a project using discarded blood in collaboration with a slaughterhouse, exemplifies Stittgen’s refusal to let things disappear without a trace. The work sits at the uneasy intersection of beauty and discomfort, presence and erasure. At a time when immateriality is idolized, his projects tether us back to the corporeal. By challenging people to detach from materiality, Stittgen demonstrates that existence carries weight, and that weight is worth preserving.

“ I was never too concerned by the visual beauty of my work, the form is there to showcase the material and create context.”

But what does it mean for something to truly exist today? Information is infinite, but attention is limited. Objects that were previously imbued with personal, cultural, or economic value—are often treated as transient and disposable. Trends cycle faster than ever, not because old things stop being meaningful, but because the system demands constant novelty. Stittgen’s work challenges this paradigm by forcing us to reconsider value—what we keep, what we discard, and why.

His approach is particularly striking in an era of hypercuration. Digital identities are built through aesthetic signifiers, reaffirming the transformation of objects into social currency. A chair isn’t just a chair, it’s a taste marker, and a symbol of belonging. Fashion, art, and design operate like stock markets, with value determined by scarcity and perceived desirability. Stittgen disrupts this cycle by centering materials that refuse to conform, such as blood, secondhand steel, and cellulose—substances that challenge our perceptions of beauty and worth simply by existing.

Beyond aesthetics, materials are political. Factors like who controls production and who decides what is waste, politicize the material world. Stittgen’s work elevates discarded matter into something sacred. His plates made from discarded cow blood in Blood Related (2017) expose the absurdity of overproduction and food waste. The material itself becomes the message, highlighting the gap between abundance and scarcity in a world built on planned obsolescence.

“The author Robin Wall Kimmerer asks the question ‘How would we treat a piece of paper if we could see the tree it comes from?’ I try to reflect on that sentence in my works by linking them back to their origin through textures and form.”

This approach cuts against the logic of mass production and fast consumption. It aligns with a larger movement of artists treating sustainability as both medium and message. In an era where artificial scarcity is manufactured through limited edition drops, or exclusive NFT collections, Stittgen’s work reminds us that real scarcity exists in the material resources we overlook.

His work also forces us to reconsider permanence. If digital objects exist forever in a state of replication, what happens to the objects that decay? Stittgen embraces the nature of the ephemeral. Notable projects such as Blood Related and Tree-ism teach us to confront the reality that objects, unlike pixels, age, and this is natural. His projects stand in contrast to technology's obsession with immortalization—whether through cloud storage, blockchain, or data preservation. Screens dominate our sensory experiences, but Stittgen reintroduces tactility This notion invites reflection on the human relationship with materials, sustainability, and transformation.

A big thank you to Basse for offering such a rich and thoughtful conversation to share with the Kive community.

BASSE STITTGEN

Learn More: https://bassestittgen.com

Instagram: @bassestittgen

Photo Credits: Basse Stittgen